The Explorer and the Aviator

For more than 80 years, historians, scientists, writers, and conspiracy theorists have been captivated by the mystery of what happened to aviator Amelia Earhart when her plane crashed in the Pacific. Now URI’s Bob Ballard, the man who discovered the Titanic, adds an important chapter to one of the greatest mysteries of the 20th century.

71.5309° W

41.4861° N, 71.5309° W

The University of Rhode Island.

October 20, 2019

Amelia Earhart remains a mystery. Bob Ballard remains undeterred.

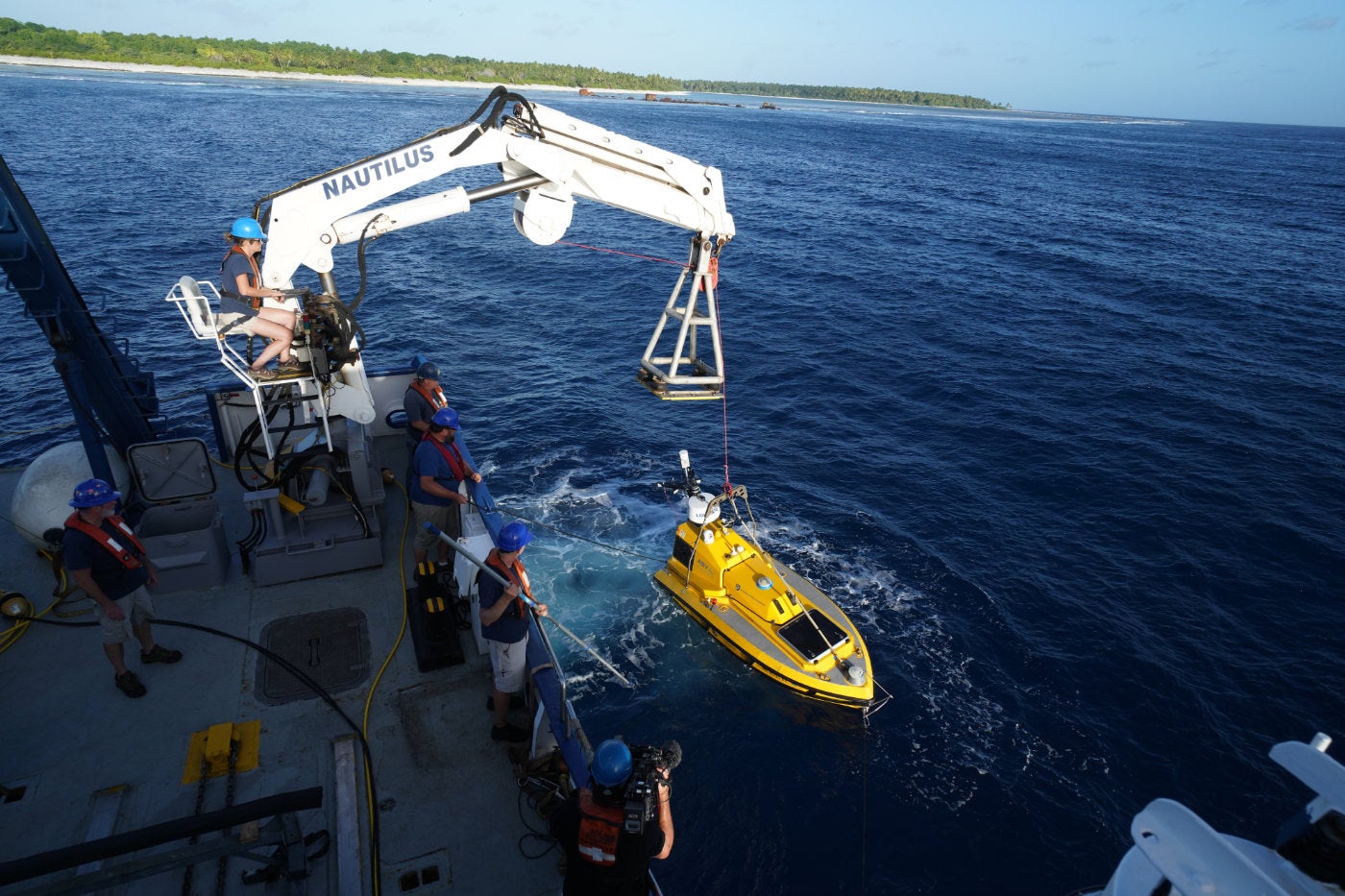

The world-renowned explorer Bob Ballard, Ph.D. ’75, professor of oceanography at URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography, founder and president of Ocean Exploration Trust, and director of the Center for Ocean Exploration, set out to find the aviator on August 6 and spent three weeks scouring Nikumaroro, Kiribati, an alleged crash site. The National Geographic Society, Ballard, and the crew of E/V Nautilus were moved to investigate by some pretty compelling circumstantial evidence: a circa-1940 photograph of what appeared to be landing gear from Earhart’s plane taken by a British officer at Nikumaroro, the bones of a potentially female skeleton found on the atoll that seemed to be a close match to someone of Earhart’s build, and the diary of a 15-year-old Florida girl who may have heard the last transmission of the famed aviator. The challenges, though, were formidable: the passage of time, the vagaries of nature, and a debris-filled seafloor.

But few, if any, explorers — ocean-going, terrestrial, or space-travelling, enjoy the fame and success of Bob Ballard (60 Minutes calls him one of the greatest undersea explorers in the world), so it seems almost a given that he should be the one to do what many claimed couldn’t be done: find Earhart, the most famous woman of her generation, and solve one of the greatest mysteries of the 20th century.

The world has been following in Bob Ballard’s wake for decades. He’s conducted nearly 160 expeditions and made discoveries of such magnitude that any single one would be enough to cap a career. In September of 1985, Ballard discovered the Titanic. In June of 1989, he found the wreck of the German battleship Bismarck. In July of 2002, he located what remained of PT-109, John F. Kennedy’s World War II patrol boat. Along the way, there were other discoveries — ancient ships in the Mediterranean and Black Seas, a fleet of World War II warships off Guadalcanal, and the U.S. aircraft carrier Yorktown.

Finding famous wrecks is just part of the story, though; and not even, Ballard said, his most important achievement. In 1977, Ballard discovered hydrothermal vents, geysers or hot springs on the ocean floor, whose emissions provide nutrients that bacteria can convert to energy in a process called chemosynthesis. Ballard also discovered a certain type of vent, black smokers, which emit water in what appear to be black plumes or clouds due to the sulfur-bearing minerals they contain. What does this matter? Well, the discovery of these geysers upended the idea that all life depends on sunlight. Finding evidence to the contrary? A big, big deal.

More on that later.

Bob Ballard hasn’t abandoned hope of finding the wreckage of Earhart’s Lockheed Electra — not by a long shot. After all, it took four tries to find the Titanic. “It’s not the Loch Ness Monster. It’s not Bigfoot,” Ballard said. “That plane exists, which means I’m going to find it.

“I’m not giving up.”

176.6183° W

0.8113° N, 176.6183° W

Howland Island, an uninhabited coral atoll, north of the equator, central Pacific Ocean, 1,700 nautical miles southwest of Honolulu, destination of Amelia Earhart to refuel before completing the last leg of her journey around the world, the morning of July 2, 1937.

Amelia Earhart and fellow aviator Fred Noonan disappeared on July 2, 1937, somewhere over the Pacific Ocean while attempting to locate Howland Island. She was to refuel there and then commence with the last leg of her trip around the world. If she’d succeeded, Earhart, the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, would’ve been the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.

Earhart was supposed to land her plane on a span of earth a mere 1.5 miles long and half a mile wide — outfitted with an airstrip secretly funded and built at the request of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt for Earhart’s one-time use. It was the Great Depression and Roosevelt didn’t think an expenditure of this sort would play well with the public.

Earhart understood the danger and reward of big risk famously saying: “[Women] do get more glory than men for comparable feats. But, also, women get more notoriety when they crash.” She proved herself right. Earhart’s successful circumnavigation of the world, a 27,000 mile trip along the equator, would have been the capstone of her career — and likely been very lucrative. Lecture series, book deals, and endorsements would have followed. And time was dogging her. Earhart and husband/promoter George Putnam saw that public interest in such daredevil acts was waning as air travel became more commonplace. In 1932, 474,000 civilians traveled by DC-3 passenger plane. By 1939, that number jumped to nearly 1.2 million.

But in July of 1937, Earhart was still hugely popular and the world waited with bated breath to know her fate in the days following her disappearance. Roosevelt, whose wife Eleanor was a friend of Earhart’s, launched the most extensive (250,000 square miles), and expensive ($4.9 million), search in United States’ history before ending it on July 18. But people have never stopped searching or hypothesizing about what happened to America’s most famous pilot — Ballard included.

“I’d been looking at the data,” Ballard said in a promo for “Expedition Amelia,” a two-hour National Geographic documentary chronicling Ballard’s quest, which aired October 20. “And, finally, I convinced myself. I’m going to find it.”

The last official communication from Earhart was heard on the morning of July 2, 1937. She was attempting to make contact with the Coast Guard cutter Itasca, which was to assist her in landing at Howland Island. The final call came at 8:45 a.m. Crewman Leo Bellarts spoke of the fear in Earhart’s voice that morning.

“I’m telling you, it sounded as if she would have broken out in a scream. . . . She was just about ready to break into tears and go into hysterics. . . . I’ll never forget it,” he later told reporters.

Then, only static. America’s sweetheart and international hero Amelia Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan disappeared over the waters of the Pacific and entered into legend.

98.4842° W

39.0119° N, 98.4842° W

Kansas, birthplace of Amelia Mary Earhart and Robert Dwayne Ballard

The story of Amelia Earhart and Bob Ballard begins in Kansas, the Sunflower State and wheat capital of the world. Smack-dab in the center of the country, Kansas boasts the windiest city in America, Dodge, and is second only to Texas in beef cattle production. And it is home to two of the greatest American adventurers in recent history.

If Bob Ballard and Amelia Earhart had been contemporaries they surely would’ve been friends. She was a bloomers-wearing tomboy who built a roller coaster for the neighborhood kids and rode a boy’s sled on her belly (young ladies’ sleds were basically chairs on runners). And she loved dreaming up exotic adventures in Asia and Africa with her crew of like-minded friends in a game called Bogie, writes Candace Fleming in her book, Amelia Lost: The Life and Disappearance of Amelia Earhart.

Ballard’s taste for adventure was whetted by reading Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. While still in college at the University of California, Santa Barbara, earning undergraduate degrees in chemistry and geology, Ballard worked part-time at North American Aviation. His father, Chet, was the chief engineer of the country’s Minuteman Missile program. While there, Ballard worked on a proposal for the HOV Alvin, a three-person submersible, to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Falmouth, Massachusetts. Years later, as an officer in the Navy, Ballard would serve as the liaison between the Office of Naval Research and Woods Hole.

To shorthand it, both Earhart and Ballard were born explorers. And Kansans. And, “a Kansan should find a Kansan,” Ballard said.

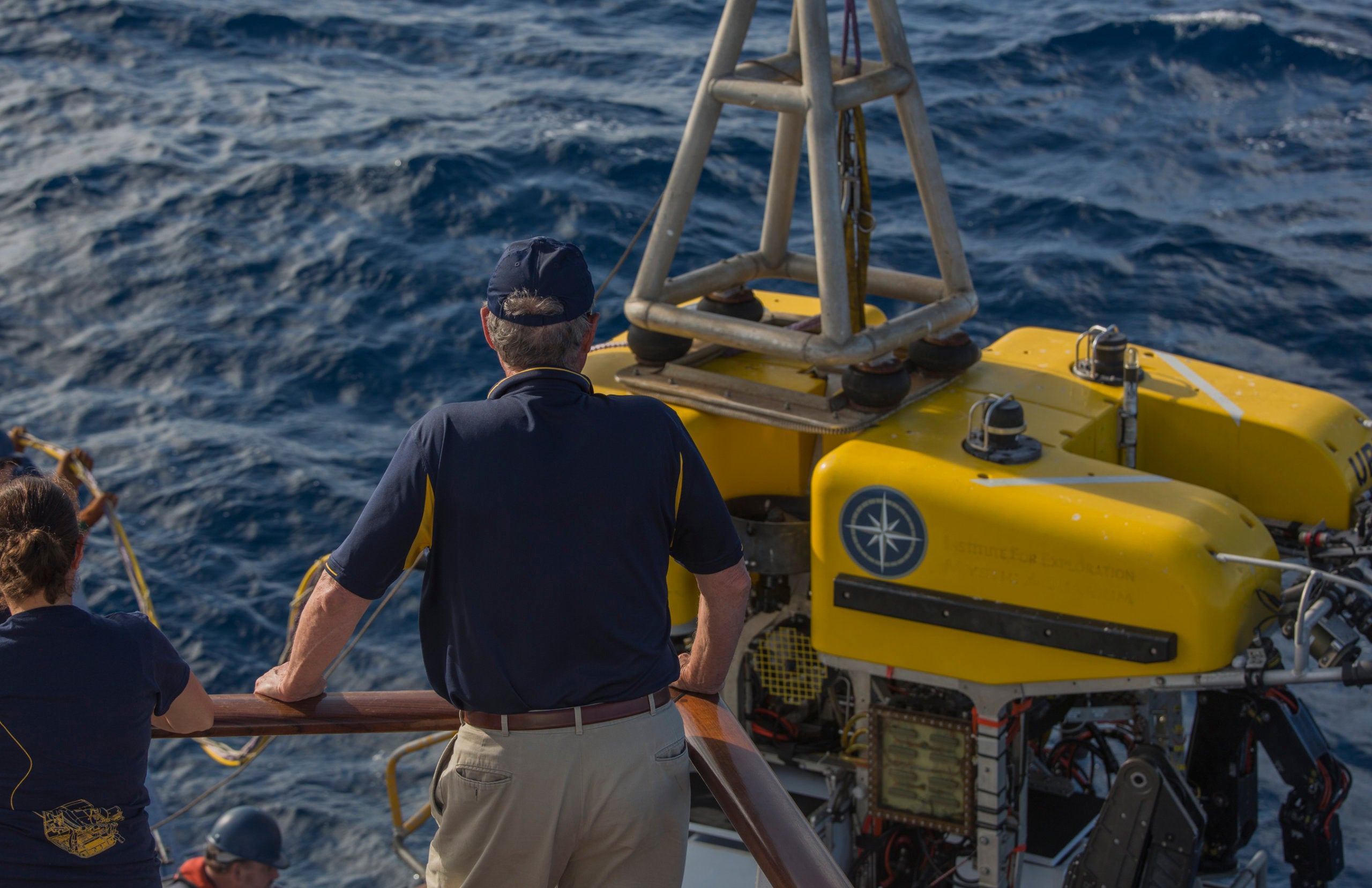

Above: Ballard and the ROV Hercules

The explorer said he owes it to his mother, Harriet Nell Ballard, to find Earhart. Like many women of her era, Ballard’s mother admired the aviator. “Amelia Earhart was an idol for my mother’s generation,” Ballard said. Harriet, a member of her high school honors society, saw Earhart’s accomplishments as a win for women. “Here’s my mom, this brilliant woman, who followed that tradition of being a housewife and was never given such opportunities.”

An aside: Expedition Amelia was an intergenerational family affair that skews female. Ballard’s daughter, Emily, was on the expedition. His wife, Barbara, intended to be, but a horseback riding injury prevented it. Also, “The team is more than 55 percent women and, you know, come on, it’s about time,” Ballard said. “Women outperform men at all levels of education. So this is really for them.”

174.5196° W

4.6779° S, 174.5196° W

Nikumaroro, formerly Gardner Island, is part of the Phoenix Islands, Republic of Kiribati, in the western Pacific Ocean, 350 nautical miles from Howland Island.

Mysteries turn epic with time, agitating the imagination like a parasite irritates an oyster, spurring the mind to overlay fact with conjecture in the hope of making meaning. And much like pearls, mysteries become treasure: tales we cherish, relish, and embellish in the retelling until we’re no longer sure what trace of truth remains.

Parsing myth from legend is difficult with Amelia Earhart. A master promoter and brand strategist long before it was a thing, Earhart participated in her own myth-making. Her husband George Putnam, publisher of Charles Lindbergh’s book We, was intent on making her the female version of Charles Lindbergh. She cut and curled her hair to achieve that tousled, boyish look, and slept and spilled oil on her leather jacket to make it looked lived in, wrote Doris Rich in Amelia Earhart: A Biography. Once, after a crash, a witness watched her touch up her makeup to be camera-ready when reporters arrived. And Earhart would, on occasion, revise her history. One biographer notes that in her memoir The Fun of It, Earhart wrote about seeing her first airplane at the Iowa State Fair in 1908, but the Wright Brothers weren’t in Iowa in 1908.

In the aftermath of Earhart’s disappearance there were a lot of leads to follow. Several civilians reported having heard distress calls from the aviator as long as five days after she disappeared. None appear to have been taken seriously by those in charge of the search.

During the 1937 search, Senior Aviator Lieutenant John Lambrecht said he saw something while flying over Nikumaroro that made him think someone might have been down there. In a report, he wrote, “Here signs of habitation were clearly visible.” But there is no record of what he saw. And the conclusion was, no one was there. Lambrecht may have made a fateful error in judgment and, perhaps, consigned Earhart to a hellish death.

The 4.5-mile-long Nikumaroro, a coral atoll, is a nightmarish place featuring brutally hot temperatures, scant fresh water, rats, foot-long centipedes, and carnivorous coconut crabs (which can weigh up to nine pounds with leg-to-leg spans of more than three feet). Sharks swim the waters around it. The atoll has always been the subject of great scrutiny as a potential crash site. In a 2015 Smithsonian.com piece titled, “Will the Search for Amelia Earhart Ever End?”, Ric Gillespie, a former pilot and aircraft-accident investigator who runs The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery, was raising money for an eleventh expedition to the South Pacific, so convinced was he that Earhart landed on the atoll. The Smithsonian article reports that in his 10 trips to Nikumaroro, Gillespie believed he had retrieved a piece of the Electra, an aluminum sheet measuring 18 by 24 inches, along with “a rusted pocket knife, bottles, zippers, and pieces of a shoe, any of which could have belonged to Earhart and Noonan, but also to any number of other people who lived on the island between 1939 and 1963.” There had been attempts to establish a permanent human presence on the island. They failed.

One account that factored prominently in the Nikumaroro theory was that of 15-year-old Betty Klenck of St. Petersburg, Florida. Klenck liked to doodle in a notebook as she listened to her father’s shortwave radio. One summer evening in July of 1937, Klenck heard a woman claiming to be Amelia Putnam (Earhart’s married name) making an S.O.S. call, saying, “Help me. Water’s high. . . . This is Amelia Putnam. This is Amelia Putnam. S.O.S.”

Static made faithful transcription impossible, but according to Klenck’s notes, it sounded as if a pair of people, a woman and a man, were caught in a small space, possibly a plane. In her notebook, Klenck noted crying and exclamations of, “I need air” and, “Let me out of here.”

As she listened, Klenck believed what she was hearing was the duo’s increasingly frantic exchange as the plane filled with water. Klenck’s transcription:

“Where are you going? Water’s knee deep,” the woman said. “We can’t bail out. See?”

“Yes,” a man replied.

“Yes,” said the woman.

“Oh, oh, ouch!” the man said.

“Are you so scared . . . What?”

For two hours, Klenck listened. She wrote, “Marie,” multiple times. Noonan was a newlywed. His wife’s name: Mary Bea Martinelli. Klenck wrote “Howland,” as well. The last thing Klenck believed she heard was water moving the plane and the woman cursing. Then, nothing.

Add to the intrigue that photo taken by the British office in 1940. Ballard had it on the authority of American intelligence analysts that the object in the water could be landing gear consistent with the make and model of Earhart’s plane.

The diary, the photo, the bones: “There was all of this circumstantial evidence pointing to this,” Ballard said.

On the basis of that evidence, The National Geographic Society, Ballard, Allison Fundis, COO of Ocean Exploration Trust and the Nautilus, mounted a multimillion-dollar effort involving air, land, and sea search efforts. The Nautilus made five passes around the island, mapping the area with multibeam sonar. A smaller vehicle scoured the shallow water around the island, and drones were deployed to explore the reef. The theory was that if Earhart’s plane had crashed there, tides would have dragged debris across the reef and heavier pieces, such as the engine, would’ve been snagged.

So what’s next? Archaeologists are awaiting DNA tests of soil samples taken from a campsite on the island. But Ballard told The New York Times that each effort that yielded no evidence felt like “nail after nail after nail” in the coffin.

Not that ruling out Nikumororo is a bad thing, necessarily.

95.7129° W

37.0902° N, 95.7129° W

United States of America.

Now-debunked theories about what happened to Amelia Earhart:

- She and Fred Noonan were American spies captured by the Japanese and later executed.

- Fed up with fame, Earhart took an assumed name, Irene Bolam, and lived the rest of her life in obscurity posing as a housewife in Monroe Township, N.J. (At least three books espousing this theory have been written. Bolam, annoyed, sued one publisher, and refuted the claim until her death in 1982.)

- Earhart, after failing to land on Howland Island, flew to the Japanese-held Marshall Islands. (The Marshalls seem invested in this scenario if the 1987 plate block of stamps issued depicting her flight are any indication.)

- After crashing, Earhart and Noonan were picked up by a Japanese trawler and brought to the island of Saipan or the Marshall Islands where Noonan was beheaded and Earhart died of dysentery. (Earhart’s fourth cousin Wally floated this theory in the newspaper The Nevada Appeal in 2009.)

- Earhart, Elvis, and Bigfoot live on in the Bermuda Triangle.

- Amelia Earhart’s plane crashed on Nikumaroro.

Grand adventures come at a price. You might fail to find what you’re looking for. You might die. But scientists keep it in perspective. “I am the same age that Earhart was when she disappeared,” Allison Fundis said. “The work gets emotional; you realize the human moments of it.

“In your excitement, you have to start to remind yourself about patience,” Fundis adds. “It took four tries to find the Titanic. The French missed it by 150 meters.”

Ballard said he has a love-hate relationship with the things he does that get him all the publicity.

“Let me tell you a little, quick story,” he said. “When I found the Titanic and went on all the talk shows and everything, my mom called and said, ‘Son, well, we’ve been watching you on The Today Show and The Tonight Show and The Day-After-Tomorrow Show, and it’s really too bad you found that rusty old ship.’”

“And I said to my mom, ‘Why do you say that?’”

“She said, you’re thirteenth-generation American. We’ve been in this country even before there was a United States of America, and you are the first in our family, along with your brother, to go to college and graduate. You’re a great scientist. You found hydrothermal vents that explain the origin of life on earth and discovered how black smokers [affected] the chemistry of the ocean, but now you’re just going to be known as that guy that found that rusty, old ship.’”

So what’s better than finding a rusty, old ship or some battered, old plane? How about leading the undersea version of the Lewis and Clark expedition?

Ballard is the lead principal investigator of the $94 million National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Ocean Exploration Cooperative Institute that will work with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to survey 3 billion acres of U.S. ocean territory over the next five years. To do this work, Ballard will have the support of the Institute, National Geographic, and URI’s Inner Space Center, which, through technology, supports live coverage of the Nautilus’ activities to the public.

“We have better maps of Mars and the moon than we do of the sea floor,” Fundis said. “This work will inform our fundamental understanding of how the planet works and affect how we make management and policy decisions in how we protect, manage, and maintain our resources.”

Without the Institute and the University of Rhode Island, Ballard said, this work would not be possible.

“We are going to be in the history books and known by the next generation as the group that mapped the 50% of our nation that lies beneath the sea,” Ballard said. “We’ll have mapped all of the American unknown by the year 2030.”

“The Inner Space Center and the whole vision that we created is why I came to Rhode Island: to implement a telepresence,” Ballard said. “Now you’ve got the R/V Resolution, our new ship, coming online. This is all about Rhode Island.”

What Ballard will find as he surveys the ocean floor of the United States is anyone’s guess. New wrecks? New species? New discoveries that challenge scientific theory? Why not? He’s done it all before.

“I’ve never grown up,” Ballard said. “I’m still that kid wanting to know why. I know that everyone else has the same questions that I have, and so I’m trying to help all of us answer these fundamental questions: Where did we come from? What are we doing here? Where are we going? And you don’t generally get an answer, just more questions. But remember that life is the act of becoming. You never arrive.

“I like really hard things that take a long time,” Ballard said with a knowing smile. He shrugs. “You have to have endurance.”

—Marybeth Reilly-McGreen